Old Rifles, New Bullets, and Chasing Perfection

By SLF Ambassador Nicolas Garcia-Cid

About 4 years ago, a buddy of mine at work said he had a Chilean Mauser. He wasn’t sure what model it was chambered in the original 7x57 Mauser, but he was looking to part ways with it. I grew up with my dad collecting Mausers, so naturally I was intrigued and told him to bring it over. I was expecting the stereotypical long barreled, lots of wood, military-style Mauser. I was surprised when he opened the case the next day and the Mauser had a sporterized stock, tapped with a scope and the original 29” barrel without the iron sights.

Having never shot a sporterized Mauser and the rifling being in beautiful condition, I bought it from him and took it home. I took the stock, scope, and the scope rings off to give it a good cleaning and to see the crest on the receiver. There, on the receiver, was the Spanish crown and Fabrica de Armas Oviedo 1925. The Mauser was Spanish, not Chilean. On inspection of the bolt I was able to narrow down to a model 1893. I ordered brass and reloading dies, followed by a search that took me down some rabbit holes when it came to bullet selection and reloading for the 7x57.

My thought was to potentially use it as my big game rifle from time to time, as I’ve grown up shooting a .30-06 for big game and nothing else. Having shot nothing but copper for big game and never having issues with it I ordered a couple different style copper bullets from Barnes, Nosler, and Hornady in 150 grains and set forth with finding a load.

Rabbit Hole Number 1:

Research showed that factory and reloading manuals have the loads scaled down due to pressure concerns. A lot of people seem to believe this is because of the “weaker” bolts on the pre-’98 mausers, but it seems like the real culprit is for the lower pressures, possibly from older rolling blocks in the chamber. Ultimately, it’s best to follow the manuals and know how to recognize the signs of early high pressure. Also, know the condition of your rifle, and if you’re not sure, get it checked by a gunsmith.

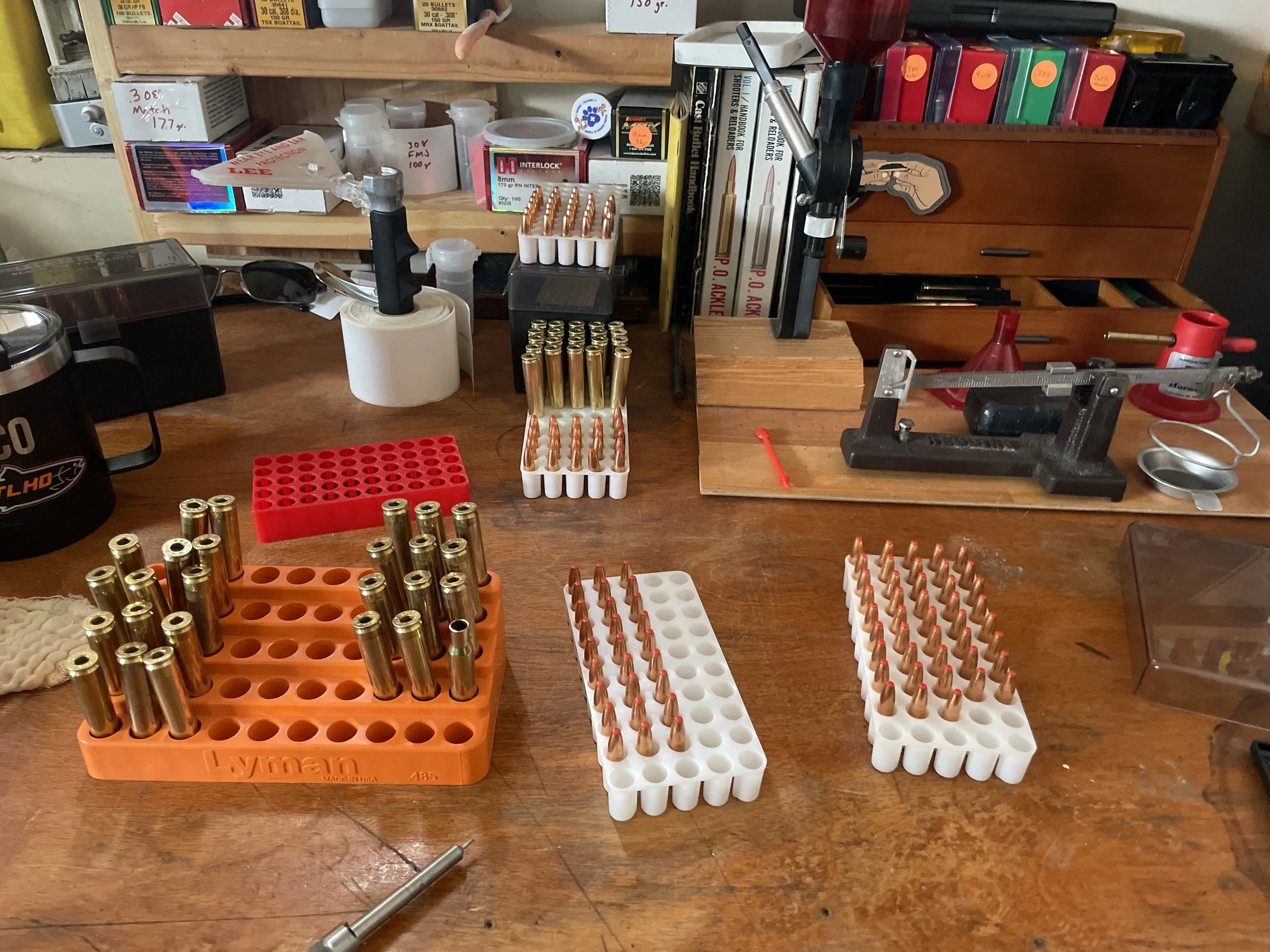

I followed the reloading manual’s charges and tried out the different ladder loads with different bullets. The groups were decent but not great, and definitely not groups I’d like to hunt with. The recoil was pleasant and significantly less than my .30-06. The velocities were right where the manuals were saying they should be, around 2700fps. Part of me thought, good enough as a range-plinking rifle, but the gentle recoil tempted me to keep chasing a load. I took a look at the bullets again and that’s where I went down rabbit hole number 2.

Rabbit hole number 2:

The original military load used for this gun was a round nose 172gr, traveling around 2300-2350fps. Armed with this information, I dove deeper into bullet shape knowing that I would be sacrificing the ballistic coefficient for a more original military shaped bullet.

Finding a “close-as-possible” round-nose copper bullet was not an easy task: Several companies make a few hollow-point bullets with a more rounded design, but it wasn’t until I was on the forums for European firearms that I found mention of a copper “round-nose” designed for the European-style chambers. Some quick googling brought me to Hornady’s ECX and in big bold words it said “THIS PRODUCT IS FOR EXPORT ONLY.” I was stumped.

Part of me thought, Oh well, I guess that’s the end of the road for that idea, and part of me thought, Canada is only about 8 hours away. By chance, I was looking at an online reloading supply website when I came across the image of the same bullet listed as “factory seconds.” All they could disclose was it was 7mm 150gr and lead-free. I checked the reviews and one confirmed it was indeed the ECX. I ordered a box of them, and sure enough, they were the bullets I was willing to drive 8 hours for just to see if it was the shape that made a difference. (On a side note with the factory seconds, I sorted the bullets and most are perfect in every way but there were a few that had slight imperfections on the tip but were still shootable. Of the 400 total I ordered, about 50 of them were what I would consider not perfect enough to hunt with.)

Again, I put together a set of ladder loads using the same powder and seating depth as the previous ones. Sure enough, I got the group down to 1”, the same size as my .30-06. Now that I had a load that was accurate, it was time to stretch the distance to see how it performed. Back at the reloading table, I loaded up a batch at the load that I was happiest with and went back out to the range.

The target was a simple 8” steel gong at varying distances out to 400-yards. Shooting from prone, the load had no problem placing rounds into the steel at all distances. So it was onto the final test: Set up eight 1-gallon water jugs in a straight line at the 400-yard target. The purpose? To catch the bullet so I’d be able to see the terminal performance at the 400-yard mark. Which brought me to rabbit hole number 3.

Rabbit Hole Number 3:

Copper is harder than lead and therefore limited by velocity. For proper expansion to occur, you have to stay above a certain speed, which is unique to the bullet. Copper bullet manufacturers list what that speed is for each bullet, but in most hunting scenarios, the game will be at distances well above that speed. With longer shots, heavier bullets with lower velocities, different barrel lengths, air temperature, and various other factors, you start to push the minimum speed limit.

Research into each bullet is imperative. I’ve seen bullets with minimum expansion velocities of 2000fps to 1600fps. Figuring out the muzzle velocity of your specific load–whether factory or hand load–is key to establishing confidence in your hunting setup. I purchased a cheap ($80) chronograph from online (nothing fancy, but it works) to track speeds. Once I have the speed, I’m able to throw everything into a ballistic calculator app that gives me theoretical velocities, along with drop and energy, at each distance. Personally, I’ll pick a distance that is 100-200fps faster than the minimum–according to the calculations–as my maximum range for a load. This is where the milk jugs come in: Once I have that distance, I set the water-filled milk jugs in a row and put a round into them. Best case scenario, the bullet doesn’t deflect out the side of a jug and stops in one of the jugs, allowing me to see how the bullet performed at that distance. If I’m satisfied with the performance, I’ll set up another row of jugs 100-yards further out and repeat the process until the bullet fails to perform. Then I back it off 100-yards as my maximum range. If the initial test proves unsatisfactory, then I move the jugs 100-yards closer. Personally, 100-yards closer or further offers more of a velocity safety zone in case I have a load that shoots a bit slower for whatever reason. Bullet performance turns into more a personal preference: For me, the bullet needs to have decent expansion and be able to pass through at least 3 water-filled milk jugs to constitute my maximum range.

Side Note on Maximum Range: If I’m taking a shot at game at my maximum range, then several trigger points need to be met.

Number 1: I have no way of being able to get closer, whether that be terrain or lack of cover to stalk closer.

Number 2: The game is not moving, preferably bedded down broadside.

Number 3: Wind has to be pretty much nonexistent, especially if the shot is going past 300-400-yards depending on the load.

Number 4: I have no doubts about the shot. I’d rather not pull the trigger and have an empty tag than risk wounding an animal.

Ultimately, 400-yards was the maximum distance for the ECX load, and then it was hurry-up-and-wait for the general deer season in Idaho to arrive. When it was time, I ended with a 4x5 plus eye guards mule deer at 146 yards. The buck was quartering away and I didn’t aim as far forward as I should have on a pronking buck. The shot entered the top of right hind quarter (luckily I didn’t lose very much meat on that hind quarter), was high enough to miss the intestines and stomach, destroyed the liver and both lungs, exited through a rib mid-ribcage on the left side, and got lodged between the hide and the next rib forward. He made it another 20-yards before collapsing, and the bullet lost 8 grains, mainly from the flat plastic tip that helps with expansion at slower velocities. Overall, I was happy with the performance in a hunting scenario and with being able to retrieve the bullet to see its performance on game, but I still wondered about getting faster velocities.

Bullet weight tends to be the biggest factor when it comes to initial velocity. You look at load data and different powders for the same bullet weight to give roughly the same velocities. This led me down a series of new rabbit holes.

Rabbit Hole Number 4:

Having always shot 150 grains in the .30-06, it seemed like a good place to start for the 7x57. However, a lot of other 7mm cartridges shoot lighter bullets for higher velocities, resulting in farther maximum distances. So I began looking for a “round-nose” in the 130-140 grain range. Unfortunately, they don’t make the Hornady ECX in anything other than 150 grains. This became more of a curiosity than anything else when I already had a load that proved itself. I decided I didn’t feel like spending the money to pursue it further.

In my searching, I came across Hodgdon’s Superperformance Powder that says it can create higher velocities (200 fps or more in some cases) without significant pressure increases. This led me down the rabbit hole of chamber, barrel pressures and friction, which brought me straight to Hammer Bullets HHT. This model is designed to reduce barrel friction but still engage the rifling effectively. These bullets are the typical pointed-ballistic-tip-style and not “round-nose” like my rifle has liked. Along the way, I came across an article about copper bullet penetration performance. Because of the ability of copper bullets to retain so much of their original weight, they perform more like lead bullets with a heavier weight in terms of penetration. For example, a 130-grain copper bullet performs more like a 145-150-grain lead bullet in terms of penetration. So now my curiosity is really itching again: Could I get a faster velocity from the 150gr ECX using the Superperformance? How would the HHT bullet shoot out of my Mauser?

I worked up a ladder for both the 132gr HHT and the 150gr ECX with Hodgdon Superperformance, wanting to see if there really was a velocity increase. The true faster velocity test came with the 150gr bullets, since I already had a load where I knew what the maximum velocity I could get out of the maximum load was, and yes, I achieved an average velocity of 193fps faster without any major pressure issues out of the maximum load. The only things of note were an increase in recoil that I wasn’t interested in and the bolt was a little sticky on opening, but no primer cratering or primer protrusion.

Ultimately for my rifle, the tightest groups with the 150 gr/Superperformance combination was the same velocity as the previous powder combination. This opened a rabbit hole into barrel harmonics, but I chose not to go down that one.

Now it was time to test the 132gr HHT loads. Velocity-wise, it was a lot faster than the 150gr load, and at maximum charge I was getting an average of 100fps faster than the published data. Again, there were no major pressure concerns. Ultimately, I settled for the tightest grouping load to further test out. Recoil was even less than the 150gr load, with an average speed of 150fps faster and a higher ballistic coefficient. More importantly, I’ve increased my maximum range, meaning that what would previously have been getting close to the minimum bullet performance velocity is now well within bullet performance velocities and on top of that, the rifle likes the HHT with 0.4” groups 100-yards off the bench.

Of course, this opens another rabbit hole or two: Is it less friction in the barrel that allows the HHT bullets to shoot so nicely when other ballistic-tip bullets with more barrel friction did not, or is it something else that I haven’t come across? Either way, I don’t think I’ll be able to test the next rabbit holes to come. In the end, I have a 100-year-old rifle that shoots tighter groups and is more pleasant to shoot than my 10-year-old rifle, so I’m not complaining.